The only regret I have about the Apartheid Museum was going after 26 hours of exhausting travel. I wish I was fully alert and rested so I could have read and processed everything more. It would be easy to spend an entire day at the museum, especially since there’s a cafe/restaurant there to refuel if needed.

.

The enlightenment

This was the best museum I’ve ever been to, filled with information that was infuriating, enlightening, and somehow hopeful. I didn’t fully understand the atrocities that occurred during the Apartheid before I entered, and the care with which the museum displayed and explained the context was truly impressive.

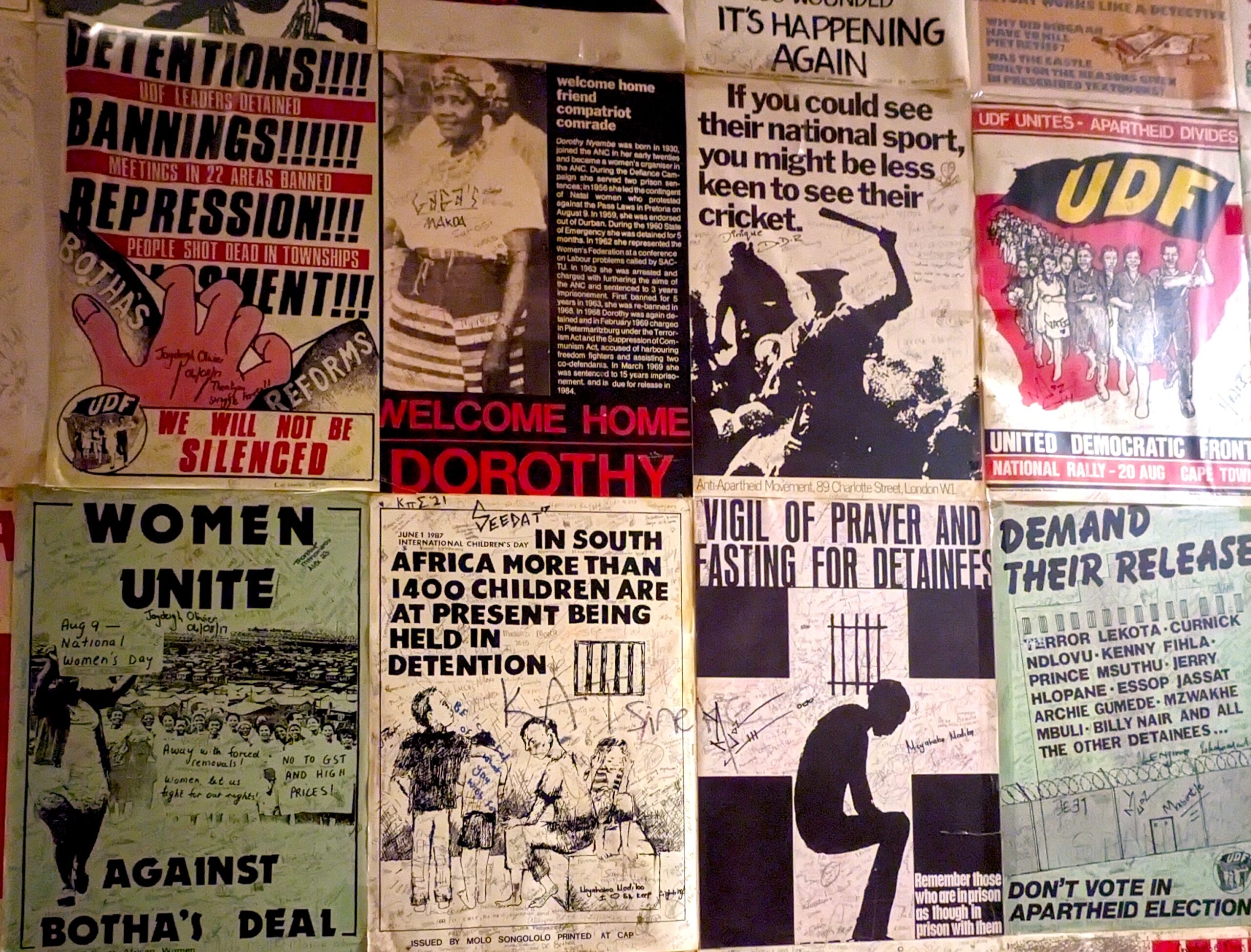

Through my visit, I constantly wondered how there was so much information about the events during this time period. Could it be the recency of the events? The existence of cameras? The eyes of the world watching and judging at the time? Were they just meticulous record keepers? By the end of the museum, it was clear that this display was apart of the reconciliation.

Shedding light on the darkness of the past is the only way to prevent it again in the future. It made me wonder how much information is classified that could ultimately help us prevent or put a stop to injustices in the world. Even the information that we have is likely “polished” beyond recognition. American textbooks often discuss slavery in a manner that glosses over the sheer horror of how slaves were treated. Native Americans receive a similar treatment, starting with how we learn about the first Thanksgiving. I appreciate that there was no glossing in this museum.

.

The truth

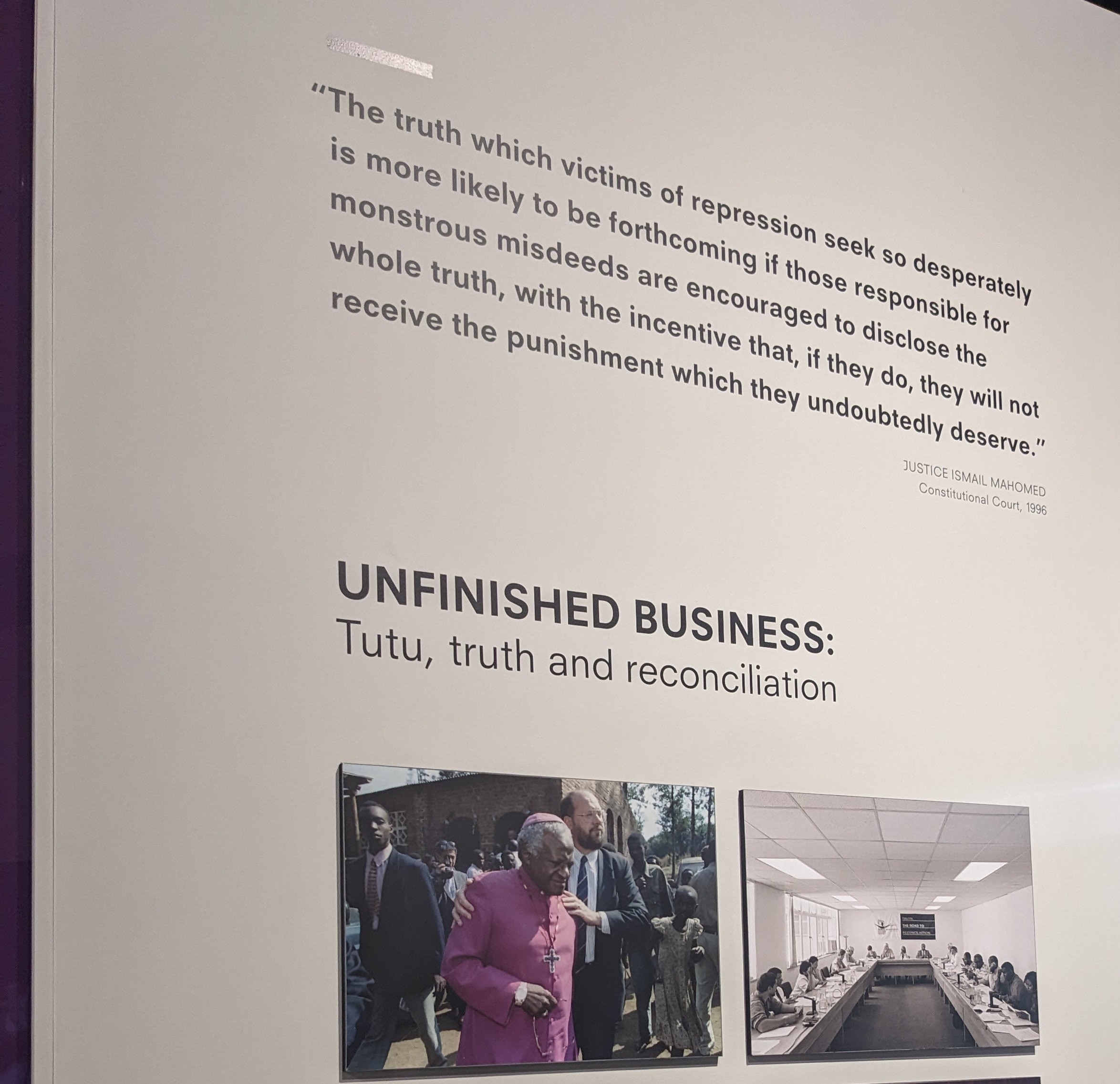

The Truth Reconcilation Committee offered amnesty to perpetrators of the Apartheid in exchange of admission for their crimes. I’m in awe of South Africans having the foresight and strength to conduct this trade. I was even more impressed at the curation of this information in the museum. This information was difficult to take in as a visitor; imagine the strength needed to create such a well-designed and informative museum.

Hindsight—and our desire for brevity—often curses us with oversimplification of the past, but not here. The nuanced, multi-faceted historical context was one that I wish we were able to see more often. Even though we don’t have the mental capacity to hold so much information about the world, the encouragement of nuance would be better…nevertheless, I tweet my opinions.

The sheer amount of firsthand documentation and accounts of the Apartheid and its aftermath was shocking. It was gut-wrenching, especially videos of the trials held by the Truth Reconciliation Committee. Watching the admission of heinous crimes to the affected parties could break someone. I watched the trial of three men in which a man asked which of the three shot his daughter point blank in a church. He broke down during the questioning, and it was a heavy thing to absorb in that dark room alone.

.

The vision

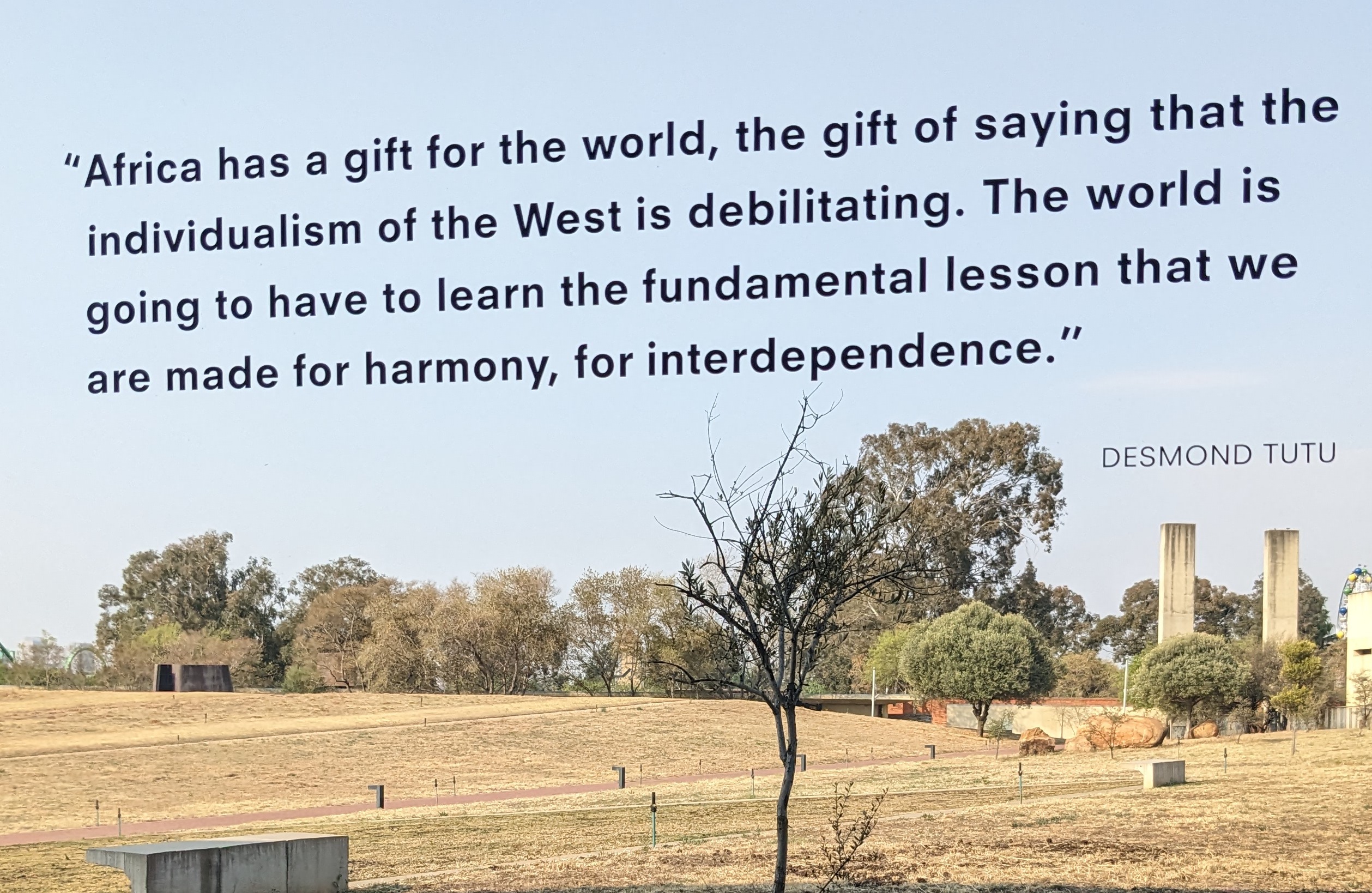

Exhibitions on Nelson Mandela and Archbishop Desmond Tutu offered a bit of refuge from the heaviness of the rest of the museum. They were still heavy, but ultimately the men held so much hope and that energy was palpable. Even so, I’m glad Tutu and I share a mutual hatred for Ronald Reagan. Tutu said he was the pits, I say may he burn in the pits of hell.

Without the Mandela and Tutu exhibitions, it would be much easier to exit museum full of despair for humanity. Mandela himself was imprisoned as long as I’ve been alive, and he was instrumental in the hope of a nation. Holding hope both in spite and recognition of the past seems much more conducive to a better future. An uninformed future is also more likely to repeat the mistakes of the past. One of many reasons history remains one of the most foundational subjects of a good education.

At the end of the museum, one quote reads, “The cost of freedom is eternal vigilance, and there’s no way in which you can assume that yesterday’s oppressed will not become tomorrow’s oppressors.” I’m not nearly as eloquent as Desmond Tutu, but I find myself thinking similar thoughts when I see Black capitalists, especially in the US and Europe—aka “first world nations.” There was even a passage in the museum about the black middle class assimilating to an oppressive system. They mentioned the desire of qualifications—particularly education—as one of the biggest tools of this assimilation. This holds true especially in the context of the US where a good education often comes at a high price.

A world in which all are truly equal means doing away with artificial hierarchies. An education can make someone more knowledgeable on certain subjects, but it does not make a better person. Likewise, money enables many opportunities, but it does not make someone inherently more deserving of them. One day, I hope we can be judged by the content of our character rather than the letters after our names, our skin, our bank accounts, etc.

.

The disillusionment

Even before entering the museum, I held disdain for many of the ways of modern life. I exited the museum wanting to change my life though. I feel a bit more encouraged to divert my energy into being the type of person I want to see in the world. Someone who embodies generosity, forgiveness, egalitarianism, and hope.

I joke about being delusionally optimistic, but maybe that’s what hope is. Mandela could have been delusionally optimistic after 20+ years in prison, but he lived to be the first democratically elected president of South Africa. It’s impossible to predict the future with any degree of certainty, so perhaps our only choice is delusion. And if optimistic delusion can pave our path to progress, who am I to shade the delusional?

Not all delusions are good delusions though, such as the American Dream. Spending much of my life in the United States did not leave me feeling united with….anything. I don’t want to live in isolation, but it’s all I’ve really known. It’s the path of least resistance at this point, and it’s spreading. Change is hard but possible, and each small sustainable change brings me closer to the person I want to be. Maybe the end goal is delusional, but there are plenty of versions in between that I would be content with.

.

The luck

South Africa is a lot like Dubai and Lisbon in that you can often see a clear difference between workers and clients based on ethnicity. In the national parks, the majority of tourists were white South Africans, and the majority of workers were black Africans. Los Angeles and New York also demonstrate this, though in lesser quantities. It’s a constant reminder of how far we have to go as far as equality and equity are concerned. For better and for worse, it’s not an isolated problem.

In many ways, I am extraordinarily lucky. I’ve visited more countries in the past two years than most visit in their lives. My job is lucrative and something I’m truly passionate about. I don’t have pressure from finances or family. I’m able-bodied, resourceful, and brilliant (and obviously modest.) It never ceases to amaze and infuriate me how much all of these factors are out of my control, yet dictate so much of my quality of life.

All of that to say that though I indulge quite a bit in life’s luxuries, I will always be in favor of reparations, restitution, and redistribution of wealth. Money is a construct and creates artificial borders and obstacles between people and their dignity. There’s a good reason many of the world’s greatest moral figures—including Mandela, MLK, Tutu—were communist. It’s the same reason fascists target communists first. Money is good in theory, but in practice is used primarily to separate the workers from the value they create.

.

The hope

Ultimately, I think the only realistic thing we can hope for the world and ourselves is to be better than we were before. Compromise is an inevitability with differing perspectives, so progress will never be as fast as we would like. This is apparent in present-day South Africa. Apartheid ended before I was born, but the divides in society are clear as day.

Change doesn’t happen overnight, and some days the only thing we can do is hope for a better tomorrow. For better and worse, we can’t predict the future. Hope is often the driving force behind our actions. Human expectations will never account for the chaos of life and its many potential outcomes.

If it wasn’t obvious by now, I spent a lot of time in the museum simply thinking about who I was, my place in the world, and who I want to be. They’re simple questions with complicated answers. And the only real answers are the actions that I take. So here’s to little steps forward in the direction we want to go.

.